- New eBook additions

- Available now

- Most popular

- Autism Awareness Month

- Childhood Classic eBooks

- Dyslexia

- Unmissable Picture Books

- Try something different

- Crime Doesn't Pay

- Novella & Short Story Classics

- Read-Along

- Out-of-this-world Sci-Fi

- The Booker Prize

- See all ebooks collections

- New audiobook additions

- Autism Awareness Month

- Books on Film

- Try something different

- Available now

- Read by a Celeb

- Most popular

- New kids additions

- New teen additions

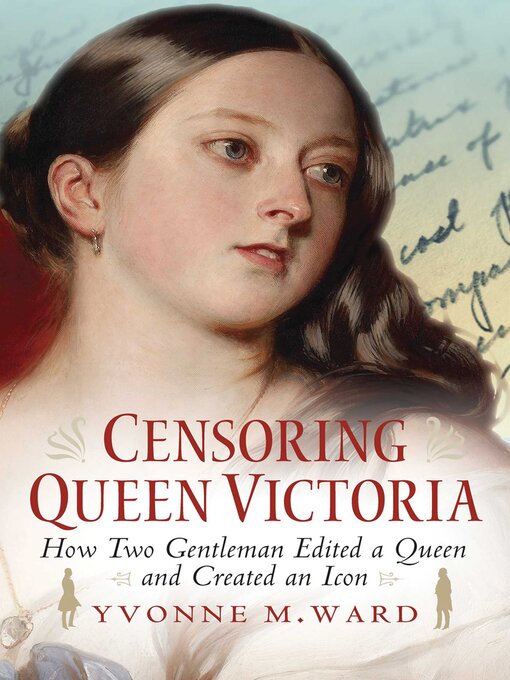

- Interesting Lives: Memoirs & Biographies

- Crime Doesn't Pay

- Popular Audiobooks

- Series Starters

- See all audiobooks collections